Can You Train Your Mind Like You Train Your Body?

Every athlete understands the importance of physical training—countless hours spent in the gym building strength, speed, and endurance. I believe the same understanding regarding importance applies to mental training, yet many athletes wonder: is it actually possible to systematically train your mind like you do your body? How exactly to go about mental training is not nearly as clear or well-understood in athletic circles as physical training methods. Is there a mental exercise—something equivalent to performing squats—but designed explicitly to strengthen your psychological abilities across multiple dimensions of athletic performance? This article wants to examine this perceived lack of understanding—namely, if an athletes actually wants to put in the work and incorporate a mental element into their training, what can they do?

Much of popular sport psychology focuses on observing how elite athletes think or feel. While this is certainly interesting and informative, it’s not quite what we’re exploring here. Similarly, athletes sometimes attend one-on-one sessions with psychologists to break down personalized psychological barriers, akin to how a coach might identify and target specific technical weaknesses in an athlete’s game. Although personalized psychological coaching has clear value, what this article aims to deliver is different: a fundamental guide of mental training principles and straightforward exercises that can be consistently practiced—much like a basic formula to improve ones vertical jump, or increase muscle size at the gym.

This guide, grounded in the latest research in sport psychology, outlines the steps to help athletes begin systematically integrating mental training into their regular athletic routine.

Where Does this Guide Come From? A Brief History of Sport Psychology

To create a practical and reliable approach to mental training, it’s essential to start from a solid scientific foundation. Historically, traditional sport psychology has offered techniques like imagery, arousal regulation, or self-talk. However, between roughly the years 2000-2010, these methods faced significant criticism for lacking rigorous empirical validation. Simply put, when subjected to more stringent testing—specifically randomized controlled trials (RCTs)—these traditional techniques often failed to demonstrate clear performance-enhancing effects.

Recognizing this problem, sport psychologists Frank Gardner and Zella Moore pioneered the integration of third-wave psychology—specifically mindfulness and acceptance-based methods—into athletic contexts. Their work marked a significant paradigm shift in sport psychology by fundamentally changing the theoretical approach to mental training in athletes. Unlike traditional sport psychology, which often implied that athletes should eliminate unwanted emotions and thoughts (such as anxiety or negative thinking) to perform optimally, third-wave psychology takes a different stance. It argues that these uncomfortable experiences—feelings of anxiety, the flow of negative thoughts, or frustration—are a natural and inevitable part of high-performance sport. Further, efforts to suppress or eliminate negative internal states can lead to psychological pitfalls, notably ‘the ironic process of mental control,’ increasing self-focused attention, breaking the flow state, and negatively impacting athletic performance. Instead, the idea of acceptance suggests that a range of experiences, including those we generally consider negative such as states of anxiety or negative thoughts, are simply part of the territory of high performance sports. Instead of trying to eliminate or suppress these experiences, third-wave methods focus on cultivating athletes’ ability to maintain task-focused attention and consistent, value-driven actions (also known as “poise”) despite their presence.

Another major theme in Gardner and Moore’s pioneering work sought to address the pressing need for evidence-based practice, moving sport psychology closer to clinical psychology standards, where interventions require validation through randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Today, third-wave sport psychology meets this criterion. Currently, at least six RCTs have examined mindfulness and acceptance-based training methods in competitive athletes, all of which reported reliable improvements in performance outcomes. Although by clinical standards this isn’t a huge amount, and each of these studies has its own problems, this makes third-wave methods the strongest available guide for athletes who want proven mental training techniques.

The Process of Mental Training Through Third-Wave Psychology

Step 1: Start doing mindfulness exercises 6 times a week

If there is indeed a mental equivalent of squats or deadlifts, mindfulness training is it. Leading sport psychology interventions, such as Gardner and Moore’s Mindfulness-Acceptance-Commitment (MAC) approach (Click Here), recommend dedicating about 10-15 minutes daily to structured mindfulness exercises. This aligns closely with routines practiced by elite athletes—Novak Djokovic, for instance, reportedly dedicates around 12 minutes each day to mindfulness practice. To get started, look around meditation apps, YouTube videos, or a quick Google search for a “mindfulness of the breath” meditation. This particular exercise is foundational in most third-wave sport psychology interventions and should be completed daily.

In Gardner and Moore’s ‘MAC’ approach, mindfulness exercises are gradually integrated into the athlete’s sport environment. After several weeks of formal mindfulness practice (such as mindfulness of the breath), athletes might begin applying mindfulness during less intensive parts of training, like stretching during warm-up. Eventually, mindfulness practice expands further into active practice situations—for instance, a basketball player might practice mindfulness while performing layups.

Mindfulness training targets the development of mindful attention and mindful awareness, these can be thought of as skills. Like a tennis forehand or serve, these skills improve only with consistent practice. Simply understanding mindfulness intellectually—without practicing it—is like knowing the perfect technique for your forehand but never spending hours refining it on court. As anyone who has taken up tennis will know, a perfect understanding of the correct form means nothing without hours of practice.

Understand, mindfulness is challenging. Keeping a mindful brain during competition will have many performance benefits, but achieving mindfulness, especially in competition, isn’t easy. Practicing mindfulness formally—sitting quietly for 12 minutes—is more demanding than merely relaxing for the same amount of time. Similarly, maintaining mindful attention during practice drills, film sessions, or repetitive tasks is far tougher than allowing your mind to drift or cutting sessions short.

The challenge intensifies during competition. Mindfulness involves recognizing distracting internal experiences—such as frustration or the impulse to give up after losing consecutive points—and observing them without judgment. It means seeing these negative thoughts simply as temporary mental events, like passing clouds, requiring no further attention. Finally, it involves repeatedly redirecting your attention back to the immediate task, such as fully preparing for the next point. During the emotional ups and downs of competition, this is undeniably difficult, it is precisely why consistent, dedicated mindfulness practice is essential for athletes serious about enhancing their mental performance.

Step 2: Understand the processes of psychological flexibility

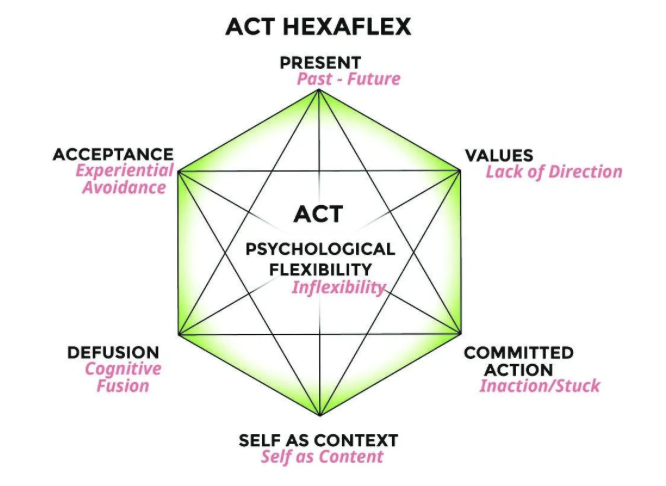

We began this article by asking a simple question: Can athletes systematically train psychological factors just like physical factors, and if so, how? When viewed through the lens of third-wave psychology, the clearest candidate for this “mental muscle” is psychological flexibility. All six randomized controlled trials that demonstrated performance improvements in athletes specifically targeted psychological flexibility. The muscle analogy works particularly well here, as psychological flexibility provides resistance against various forms of experiential avoidance, which tries to pulls athletes away from ideal performance states and actions like a strong tide. Fortunately, psychological flexibility can indeed be trained and strengthened through deliberate practice. Mindfulness training, for example, directly enhances two key components of psychological flexibility: defusion and present-moment attention (see below).

Psychological flexibility is the central target of third-wave interventions like Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). It’s highly practical and directly applicable to sport and performance psychology. This concept breaks down into six core components: Acceptance, Commitment, Defusion, Present-moment awareness, Valued-action, and self-as-context. Improving any of these areas enhances overall psychological flexibility. It is important athletes develop a grasp of these six processes at some level of theoretical understanding. This knowledge will provide a starting point for how psychological factors can influence performance in both competition and practice.

To deepen your understanding of these six psychological processes and their practical implications, beginner-friendly books (Click Here), podcasts, and websites are readily available, offering accessible and actionable insights into psychological flexibility. Third-wave programs such as the MAC, tend to focus on one or two aspects of psychological flexibly a week (it is a 7 week program). This involves various exercises for each component and a strong emphasis on the session leader to make sure clients have a strong theoretical comprehension of the concept.

Step 3: Understand psychological flexibility experientially

How are the processes of psychological flexibility experienced? Cultivating an experiential understanding means developing an intuitive awareness of psychological flexibility in real-time, from a first-person perspective. How does it actually feel to experience processes like defusion (or its opposite, cognitive fusion)? This experiential knowledge involves recognizing when attention begins to drift or when your behavior is on the edge of diverging from your performance values or goals. An experiential understanding bridges the gap between theoretical concepts of psychological flexibility and the practical ability to apply these concepts directly in competitive situations.

Starting a mindfulness practice (step 1) can help bridge the circle between theoretical and experiential understanding. When we practice mindfulness, we are building the skill of mindful awareness. This can help develop increased experiential understanding of the nature of the mind, and specifically those moments when the pulls away from our performance values and state need to be resisted.

Step 4: Practice mindfulness and psychological flexibility in sport and training

In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle famously describes moral virtue as similar to a skill developed through repeated practice. The concept of consistently practicing valued-actions is likewise central to contemporary psychological models such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)—the foundation upon which third-wave sport psychology is built. As athletes deepen their mindfulness practice and understanding of psychological flexibility, they become increasingly aware of critical moments during performance when psychological flexibility defines two distinct paths. One path leads toward functional performance characterized by focused attention and committed actions—essentially “following the process.” The other path leads toward dysfunctional performance, marked by losing focus or taking shortcuts that undermine athletic success. It is precisely in these moments that an athlete can practice, and in turn strengthen psychological flexibility.

References

Dehghani, M., Delbar Saf, A., Vosoughi, A., Tebbenouri, G., & Ghazanfari Zarnagh, H. (2018). Effectiveness of the mindfulness-acceptance-commitment-based approach on athletic performance and sports competition anxiety: A randomized clinical trial. Electronic Physician, 10(5), 6749–6755. https://doi.org/10.19082/6749

Gardner, F. L., & Moore, Z. E. (2007). The Psychology of Enhancing Human Performance: The Mindfulness- Acceptance-Commitment (MAC) Approach. Springer Pub.

Gross, M., Moore, Z. E., Gardner, F. L., Wolanin, A. T., Pess, R., & Marks, D. R. (2018). An empirical examination comparing the Mindfulness-Acceptance-Commitment approach and Psychological Skills Training for the mental health and sport performance of female student athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(4), 431–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2016.1250802

Josefsson, T., Ivarsson, A., Gustafsson, H., Stenling, A., Lindwall, M., Tornberg, R., & Böröy, J (2019). Effects of mindfulness-acceptance-commitment (MAC) on sport-specific dispositional mindfulness, emotion regulation, and self-rated athletic performance in a multiple-sport population: An RCT study. Mindfulness, 10(8), 1518–1529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01098-7

Lundgren, T., Reinebo, G., Fröjmark, M. J., Jäder, E., Näslund, M., Svartvadet, P., Samuelsson, U., & Parling, T. (2021). Acceptance and commitment training for ice hockey players: A randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.685260

Sabzevari, F., Samadi, H., Ayatizadeh, F., & Machado, S. (2023). Effectiveness of mindfulness-acceptance- commitment based approach for rumination, cognitive flexibility and sports performance of elite players of beach soccer: A randomized controlled trial with 2-months follow-up. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.2174/17450179-v19-e230419-2022-33

Leave a Reply